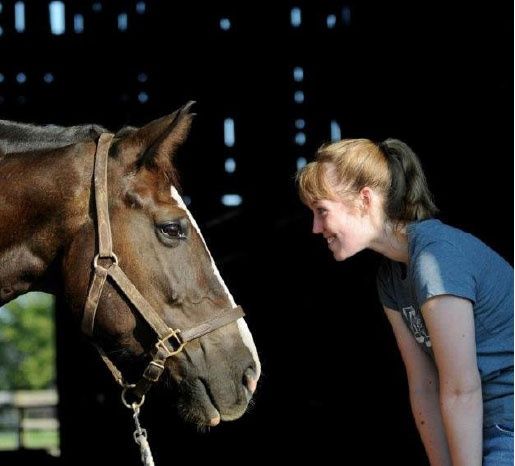

The most difficult decision horse owners ever make

The hardest part of horse ownership is the end of your journey together. For most of our horses’ lives, we try not to think about the fact that we will likely outlive them. But I firmly believe that part of responsible ownership is having a plan for when the end comes.

It’s relatively uncommon these days for a horse to die of natural causes, which means at some point you, together with your veterinarian, will need to decide when it’s appropriate to euthanize. If you’re keeping a horse for its lifetime, it’s best to think about your end-of-life plans for that horse well before you need them. Many people put this off until the horse is older, but you need to have a plan in mind regardless of the horse’s age. Young, otherwise healthy horses can meet untimely ends thanks to anything from colic to laminitis to paddock accidents to lightning strikes.

Your life together

The first thing you should have in mind before this moment comes is what you consider to be an acceptable quality of life for your horse. This definition can be especially helpful when you’re dealing with a situation of chronic, nagging medical issues.

Too often, when animals decline gradually and you see them every day, it can be hard to really assess how they’re doing. This is also why yearly examinations by your veterinarian can be helpful, especially if they see the horse infrequently – gradual changes in the horse’s condition will be more obvious to an expert who hasn’t seen them daily.

Fortunately, the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) has created a checklist to help. This list includes the provisions that a horse should not have to endure any of the following: continuous or unmanageable pain, medical condition or surgical treatment with a hopeless chance of survival, an unmanageable medical condition which makes the horse dangerous to itself or others, continuous analgesic medication for pain relief, or continuous stall confinement to prevent pain and suffering.

These standards are also in accordance with the American Veterinary Medical Association’s definitions for animal euthanasia.

Consider life from the horse’s perspective, not your own

Is he able to comfortably walk outside, eat and drink without pain? Will further medical treatment put him through considerable suffering and anxiety with minimal chances of success? For a domesticated horse, these are the most basic elements of daily existence.

As always, consult with your veterinarian on these points.

Your own critical eye

Making the decision to euthanize can be difficult. One thing veterinarians and equine welfare advocates strongly discourage owners from doing is passing that decision onto someone else.

Many say they see older horses show up at livestock auctions, rescues, or in neglect situations because the horse’s last owner was unable or unwilling to honestly assess the horse’s quality of life and preferred to believe it would find a home as a children’s horse or pasture puff for a few more years.

The trouble is, the number of older horses or those with athletic limitations far exceeds the number of homes able to take them, and too often this results in a horse’s final years being spent in neglect or abuse.

After the decision is made

Once you’ve made the decision to euthanize, have a conversation with your veterinarian about the practical considerations. You’ll need to be prepared for the cost of euthanasia, which can be quite high in some parts of the country. Some non-profits offer free or low-cost euthanasia clinics for horse owners who can’t afford it, but availability of these can vary.

You’ll also need to consider the disposal options for the horse’s body after euthanasia. It’s best to do this in advance of the decision.

Local and state governments are often highly restrictive about burial of horses or other livestock species, with particular concern toward their proximity to waterways and wells. Beyond this, burying a horse deeply enough (a trench of at least seven feet wide and nine feet deep is considered sufficient) requires special equipment like a backhoe, which can be rented for several hundred dollars.

Veterinary teaching hospitals have access to incineration or cremation facilities that accept horses. Costs can range up to and above $1,000

For many years, horse owners without access to cremation or burial would send the carcass to the local rendering plant, where it would be boiled down to elements such as bone meal and blood meal that are used in landscaping or animal feeds. Recently, however, several cases of dog foods tainted with euthanasia solution has put most rendering plants off of accepting animals that have been chemically euthanized. (Many plants process a variety of species, and therefore cross-contamination is a concern, even for species not used in dog food.) Some landfills have a special section for animal remains, and some will still accept chemically euthanized animals.

Whatever option you choose, you’ll want to consider transportation as well.

There’s no question your last goodbye with your horse will be difficult, but you can make it easier on yourself is taking some of the decision making out of the equation early.

Tags:Horse Sense

Acreage Life is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.