Readying your mini-farm for colder temps

Labor Day has come and gone, the kids are back at school, and—is that an orange leaf floating through the air? Fall is a sure sign that winter will be here before we know it. As tempting as it might be to scoop into another slice of pumpkin pie and ignore the reading on the thermometer, autumn is also a good time to make sure your barn, pasture, and livestock are ready for the chillier temperatures.

In the barn

Depending what part of the country you live in, the barn or structure where you keep your animals might not have originally been intended to shut out the winter winds.

“One area many horse owners worry about is the temp in the barn come winter,” said Robert Coleman, PhD, assistant professor of equine extension at the University of Kentucky. “They will often close up the barn to keep-in warm while reducing or eliminating air flow and having a negative effect on the air quality.”

Poor air quality predisposes all species to respiratory illness, and isn’t likely to do you any favors, either.

Keep in mind that horses and cattle are designed to withstand cold temperatures by using their built-in furnaces. They increase their feed intake and use the heat generated from digestion to keep warm. Harsh winds and moisture draw that internal heat away from the animal more than low temperatures alone, meaning they need shelter from the elements, not the cold itself.

Chickens do not have the same internal furnace system as cattle and horses, and will probably elect to spend more time inside whatever structure is available to them. Sealing cracks will help keep in warmth, but you need to allow for ventilation here also. The chickens will likely produce more litter indoors than usual, so prepare with a quality bedding material like pine shavings, and be ready to change or pick the bedding in your hen house more often.

Experts say many people worry about the safety of heaters or heat lamps in barns. Generally, heat lamps are safest if hung high enough that animals can’t knock them over, and if they are not placed over straw or other easily flammable bedding. Many barn fires traced back to heat lamps have begun in the middle of the night, so limiting their use to times when you are in the barn could be safest. Space heaters can pose similar dangers in tack or equipment rooms: Coleman suggests checking the wiring and cleaning the heaters before it’s time to use them. Dusty heaters are not only prone to fire, but are also less efficient. Also check whether your electrical system can handle the load of the heater before plugging it in.

One of the most critical considerations when managing animals in any season is access to water. Automatic waterers in the field will freeze last because the water supply is kept in motion. Some types have rubber floats that animals must push down in order to reach water, shielding the supply from cold temperatures at the surface.

If you don’t have an automatic waterer, look into tank heaters for outdoor water supplies. Inside, heated buckets can be helpful. The older metal heaters that are placed inside full buckets may not have thermostats in them and can overheat water or pose a fire risk if left sitting for more than a few minutes. Most farm supply stores now carry buckets with a thermostat and heating element in the bottom of the bucket. These are designed to just keep the water above freezing, and shut off periodically.

“When it gets cold, thawing water sources can take a long time. If people were going to do some winterizing in the barn, that would be the place to spend the time and effort,” said Coleman.

Heat tape can help warm pipes in unheated interior rooms, like tack or supply closets. Heating tape comes with temperature control devices to prevent overheating. Manufacturers recommend inspecting installed tape to check for kinks or tears before the season begins.

As many farmers learned during last year’s harsh winter, even heated or automatic water elements will freeze if it gets cold enough. Be prepared to check on water supplies a few times a day in harsh temperatures.

Pasture

For your pastures to come out of winter in good shape, they need to go into winter in good shape.

“The fall is a good time to walk the pasture and assess weeds and how good the stand of grass you have is. Early September is a good time to over-seed if needed,” said Coleman.

At this point in the year, competition from weeds should be fairly low, so it’s a good time to cover over bare or thin spots in your fields in preparation for next year, a process called overseeding. Extension specialists recommend doing an inexpensive soil test (which is typically available through your state’s land-grant university) to determine what minerals you’re lacking. Apply lime or fertilizer as needed before putting down seed. It’s not advisable to put down nitrogen at this point in the year, as it could leech into ground water. Use a liberal amount of high-quality seed with no-till drill seeding if possible.

Mowing or allowing your field to be grazed closely will help reduce competition from weeds, helping new plants to thrive.

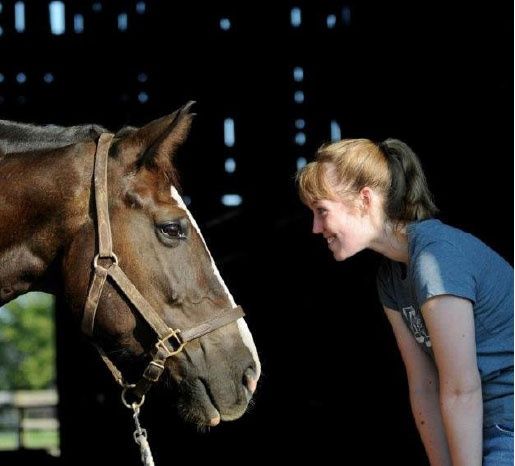

Animals

Horses, cattle, sheep, and goats will grow thicker, longer haircoats to prepare for the winter season. You may begin noticing changes in your animals’ coats in fall, as their brains take note of the shorter day length as a sign of things to come.

For owners of competition horses, blanketing can be a good way to stave off the puffer-fish effect that comes with a thick winter coat. Remember that you’ll need to start blanketing early, and to always use sturdy, waterproof sheets when your horse is outside. If you’d rather not keep up with changing sheets with the weather, your horse should be fine unblanketed as long as he has shelter from the rain and extreme wind.

Although the insect population will be fading out as the temperatures drop, you’ll likely see more of another pest: rodents. They will come inside to get out of the cold, so fall is a good time to reassess your feed storage protocols. Even if you have a legion of barn cats, mice will do what they can to chew through paper bags or even wood to reach feed or supplements. Storing your animals’ feed in plastic or metal bins can keep the little fiends out. Heavy plastic trash cans with raccoon-proof tops are an inexpensive choice.

Sealing holes in your henhouse, if you have one, can discourage rodents from sneaking in and taking the chickens’ dinner. (See “I Smell A Rat” on page 20 for expert tips on shoring up your coop.)

If you’re really having issues with mice, considering laying a few traps for them.

“It would be a good time to take measures to control them, including sealing holes in the structure and placing rodenticide in bait stations around or inside the building,” said Cantor. “The bait stations should be the type that prevent not only chickens, but also cats and dogs, from eating the rodenticide.”

Plan for your animals to eat more as the weather gets colder, too. Fall is the ideal time to stock up on hay before prices rise with the demand later on—just be sure you’re ready to properly store it.

“Make sure the hay is dry when you store it to avoid problems with spontaneous combustion,” said Coleman, who said research shows moisture content of 16 percent or less is best to prevent mold. “Store the hay on well drained ground and if you can get it off the ground, that is better. Cover the hay to protect it from rain and snow. This can be in a hay storage facility or covered with a tarp.”

Not covering the hay can put you at a risk for losing part of your supply, and research indicates that the cost of building a structure or purchasing a tarp for the hay is less than the cost of the bales likely to be lost due to the elements.

Plan for animals who are receiving grain to get larger amounts or higher-calorie concentrate to compensate for burning extra calories with their internal furnaces. For cows and chickens, adding a little cracked corn to the diet can be helpful, as it will provide an inexpensive source of heat.

Although hoof growth will likely slow down for most animals in winter as the lush grass dies, they will still need regular trims. Many people prefer to remove their horses’ shoes through the winter season if they live in colder climates where they will be riding less. Discuss shoeing changes with your farrier or veterinarian to determine what’s most appropriate for your area. In regions where the ground stays frozen for extended periods, you may need to have the shoes pulled in fall so the hooves can adjust; in warmer, rainier places, mud and moisture might be more prevalent, which could change your horse’s needs.

Parasites will be growing much more slowly in winter, but don’t think they’re completely dormant. Consult your veterinarian about timing regular wormings—especially toward the end of winter as animals prepare to give birth and before the soil warms up.

Equipment

Don’t leave your farm equipment off your winterizing to-do list. Check the coolant levels in your truck and tractor, and make sure your block heaters work, if you have any.

Fall is also a good time to think about getting a back-up generator for your farm.

Your friendly neighborhood cooperative extension specialist is a great resource for other questions about preparing your farm for winter. Find your nearest extension office at www.csrees.usda.gov/Extension.

Tags:Seasonal Living

Acreage Life is part of the Catalyst Communications Network publication family.